This post is similar to some others on this website, but is different in that it offers only my family’s preference of convenient beef items and it does not go into spelled-out recipes. Complete recipes and procedures are explained in some other Meat Mentor posts. Feel free to ask for more information if interested in any of these processing practices. The following information is targeted to help out either frugal home meat processors or those wishing to operate specialty item meat shops.

This pic documents the highest per pound price that I have ever had to pay for a retail priced, wholesale case of Choice chuck-rolls. The label reads chuck-eye, but a true chuck-eye is actually just one section of a beef under-blade. The whole under-blade is commonly termed chuck-roll. Despite being at an all time high price, this case was also “short-cut” to boot. The “short cut” harvest plant practice leaves more chuck weight on the higher priced wholesale beef rib and therefore less weight on the chuck-roll.

I recently conducted a poll in a Facebook butcher’s group and came up with a just over $4 per pound National average on Choice Quality grade 80-20 ground beef. Since $4 per pound is right at what I paid for Choice chuck-rolls, grinding the entire boneless chuck-roll case could reasonably be viewed as being both a time and money loser. However, knowing exactly what was ground and how the meat was trimmed prior to grinding are both upside considerations to me. In general, I prefer to start out with raw unenhanced meat so that I will know where all my finished product originated from.

Luckily, I was able to produce almost as many pounds of Choice ground beef as the case of chuck-rolls weighed, and while gleaning 74 pounds of Choice beef cuts from the 2 purchased wholesale cases of beef. Admittedly, about 13 pounds of the 74 pounds of cuts came from 2 eyes of round. After robbing lean closely trimmed chuck cuts, delicious chuck fat trim was left and ground with the one muscle Choice eye of round. The fat chuck trimmings were a great edition to otherwise overly lean/dry ground round. The 85 pound case of eye of round substantially lowered my starting raw per pound meat costs, but trim fat and bag purge losses then pushed my useable Choice beef cost up to $3.48 a pound. 54% of usable starting raw Choice beef was made into premium ground beef. The remaining 46% was made into London broils, cube steaks, stew beef, beef for stir-fry, Lunchmeat, roast beef or jerky.

If you buy a bone-in side of beef from a hobby farmer who raises heritage beef breeds, you might well end up with a low meat yielding fat cattle carcass; like the rib steaks pictured above. If that happens, don’t blame the custom meat processor for your low yield of edible product. Further, some grass-finished cattle carcasses may be of maturity levels that are predictive of tougher meat. Long beef carcass dry-aging periods are often practiced to enhance the desirable flavor development and tenderness of “grass-fed” (might be grass-finished) beef, but cooler shrinkage and trim loss will then increase; plus the entailed breaking down of meat protein and fat oxidation can make for potentially less healthy end-product. A product yield advantage of buying boxed beef is that the big packers have fat trim specifications; so high number carcass Yield grades should not then show up much as retail trim losses. Big packers discount the price paid to feedlots for High numbered (low yielding) Yield grades.

For what actually goes into freezer storage, a run-of-the-mill, grain-finished, usually ungraded, freezer side can easily run a dollar or more per pound than my current $3.48 beef hack price. It’s true that a side purchase provides “middle-meats” loin & rib steaks, but cuts from custom processed sides also routinely contain bone & table trim-fat that end up not being eaten. Another distinct advantage of beef hack nirvana is that we buy only what we like to have conveniently on-hand in home freezer storage, with the exception of an occasional rib or loin steak. I make a habit of doing non-meat grocery shopping fairly early on Sunday mornings. Saturday is the highest volume grocery shopping day of the week; so there’s normally a good selection of marked-down steaks between 7 and 8 o’clock on Sunday morning. Those retail trimmed steaks can either be eaten that day or be immediately frozen for the short-term. No more than we eat middle meat steak, our total averaged beef expenditures of closely trimmed boneless beef likely remains well below $4 per pound. And as already mentioned, $4 per pond is a little under the average National retail price of Choice Quality grade ground beef. Point of interest: The vast majority of retail ground beef is mostly made from culled breeding stock (lower eating quality).

Value-added processing:

The cut fabrication or further processing of some of the following meat items overlapped at times in this post, but often the production of each item will be presented pretty much from start to finish.

Here the 4 chuck-rolls that were in a case are seamed-out into muscle groups; one chuck-roll was noticeably smaller. The nearest cuts in this picture are the Denver steak muscles. The little pile next to the small Denver steak muscle is the tapered rib-eye ends that remained after the short-cutting of the chuck-rolls. The true chuck-eye rolls are in the center of the kitchen island. And, all the flat chuck-roll muscles are farthest away.

Denver steak muscles were trimmed up then split along the natural vein line.

The tapered, thin end of the Denver steak muscle was lopped off and the 2 thicker pieces were cut in half thickness wise to produce high quality London broils. If left at their full thickness, Denver steak muscles plump way too much during high heat cookery to cook to the target internal temperature before the outside burns.

This shows 1 of the 2 separated sections of a Denver steak muscle about to be cut in half thickness wise.

Here are 2 of the 16 total London broils that the 4 Denver steak muscles yielded. After cooking they slice nicely across the meat grain; similar to how flank steaks are cut for serving.

Beef for stir-fry cut from the tapered end of one Denver steak muscle, and some of it was from squaring-up the 4 London broils that were generated.

Beef for stir-fry, from all 4 whole Denver steak muscles, heading into freezer storage. These packages can easily be finer diced while still in a partially frozen state.

I cleaned up and cubed all the tapered rib-eye ends; then salted and peppered them. We had medium rare steak cubes and eggs for breakfast.

9 pounds of clean chuck-eye roll and 1 pound of flat muscle for the later making of a lunchmeat beef roll.

A little under 9 more pounds of chuck-eye cubed up for stew beef, it was immediately packed and frozen.

A deep steam table pan, 3/4 full of fat chuck trimmings.

24 portioned pieces of flat muscle from the chuck-rolls; to make cube steaks. 3 more packages of stew beef obtained from the flat muscles can be seen at the top of this picture.

24 individually packaged cube steaks heading to the freezer. When any of the flat muscles were much over an inch thick I butterflied them prior to cubing then folded them back together for the last pass through my new $80 hand crank cuber.

12 eye of round that were in the 85 pound wholesale case. I picked out the biggest one to make roast beef and the second biggest went for jerky production.

A 6 pound denuded eye of round for jerky.

Jerky eye of round cut in half lengthwise then into slabs. Raw meat was then placed on a cookie sheet and put into the freezer to get it semi-frozen to facilitate knife slicing.

Meanwhile, the largest eye in the case was trimmed a bit then pumped for making roast beef.

Raw roast was covered and placed in 170F oven to cook to 130F internal.

Cooked roast was browned under the oven broiler then chilled overnight.

Knife sliced roast beef.

Sliced roast beef packaged and going into the freezer.

Partially frozen jerky meat was sliced and mixed in with a cure containing marinate.

Jerky was dehydrated the next day in a 6 tray circular countertop dehydrator.

It took two, 8 hour runs of my little dehydrator to adequately dry out the 6 starting-raw pounds.

Here, most of the finished jerky was double bagged and placed into the freezer. Some had already been eaten.

The 9 pounds of clean chuck-eye (shown earlier in a large white bowl) was ground once through a 3/4 diameter plate and the 1 pound of flat chuck-roll muscle was ground once through a 3/16 inch plate. Both grinds were mixed together as the meat component of a lunchmeat chub.

While grinding, I made Choice ground beef at that point in time. Pictured is half of the eye of rounds; that have been fatted-down and cut into strips that will easily feed through the meat grinder.

I really like the one muscle, lean meat characteristics of the eye of round, but always freshen the surface of their subcutaneous fat. That fat was exposed on the kill-floor and is normally somewhat discolored from both kill-floor exit steam cabinets and later by a spray-on organic acid microbial intervention. I’m thinking that the washed-out dark spot in the above picture might be steam cleaned manure. E-coli is fecal borne; so trimming and discarding the exterior surface of subcutaneous fat is a good precautionary practice. I recall reading a meat magazine article about e-coli in the early 1990’s where an interviewed small beef plant manager said “basically they are now telling us that it’s OK to eat shit as long as it’s cooked shit.” Another reason that the amount of subcutaneous fat on the eye of rounds was reduced was because I did not want the ground beef to be overly fat. Further, I prefer fat chuck trimmings over round fat. Another good thing about chuck-rolls is that none of their exterior surface is exposed while on the kill-floor.

This fat, plus a bag purge estimate, was my 6 pounds of loss that was used to calculate a $3.48 per pound starting raw beef price.

Here are 2 lugs of eye of round strips with the meat from 5 eyes in each lug. And, the fat chuck trim was somewhat equally divided on top of the eye meat. The multiple small muscles of the beef chuck provide a lot of flavorful collagen and seam fat. Everything was then ground once through a 3/16 inch plate; while alternating between lean and fat as grinding progressed.

All grind was mixed back and forth, using two lugs, to achieve a fairly uniform fat & lean distribution. This pic shows all 82 pounds thrown in one lug at the end of hand mixing.

Here is one sandwich size package more than half of all the Choice ground beef. It was placed in the freezer than I packed-off the second two thirds of a lug of Choice ground beef.

Lunchmeat chub meat was mixed well with the non-meat ingredients then hand stuffed in a semipermeable large fibrous casing. Chub was then cooked in a covered roasting pan at 170F to 155F internal.

Casing was striped immediately after cooking, then with the lid off the chub spent a few minutes under the oven broiler to obtain a more desirable color.

The bind was good in the chub and it nice sliced nicely after being fully chilled.

Double wrapped packages of sliced lunchmeat heading to the freezer. The ends were immediately made into a corn beef hash like entrée.

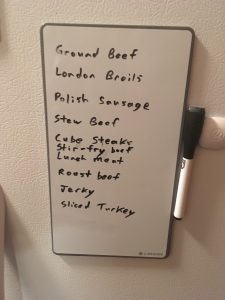

A dry-erase board on our uptight freezer to let my wife and 3 grown, and moved out, children know what products are currently in freezer storage.